The Ambassador: How Good Works Can Be Done in Public and Private

Actor Tommy Dewey played John Emerson in the 2018 political drama The Front Runner. The film stars Hugh Jackman in a highly dramatized rendering of the undoing of one of the most enigmatic, and influential, figures in post-Reagan-era politics: Gary Hart. Emerson became the Hart campaign’s California chair in 1984, and then deputy national campaign manager in 1986, after being inspired by Hart’s Kennedy-esque bearing and forward-facing reimagination of the Democratic Party as a Gen X-friendly coalition of socially progressives, environmentally conscious, college-educated professionals.

Hart’s campaign famously imploded when the enviably maned Colorado Senator got caught in an extramarital affair with the much blonder and younger Donna Rice. Asked how he liked his portrayal, the famously equanimous and quick-witted Emerson joked, “Oh, he’s a really good-looking guy, so it was fine with me.”

Emerson’s involvement with politics didn’t end with Hart. In the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, when California politics, particularly Southern California’s, was far from the deep blue hue it is now, the first stop for national Democrats looking to make inroads was Manatt, Phelps, & Phillips. The powerful Los Angeles law firm’s founder, Charles T. Manatt, had chaired the Democratic National Party and it’s there that Emerson first got exposed to and inspired by Hart’s cosmopolitan-yet-common sense politics.

Emerson joined Manatt, Phelps & Phillips in 1978 after getting his law degree from the University of Chicago Law School. He was born in Chicago but grew up in the New Jersey and Westchester County suburbs of New York City and attended Hamilton College way upstate New York. It makes sense that his compass was set due west, though. Emerson’s father, a minister, grew up on the Stanford campus where Emerson’s grandfather was a professor. Emerson’s mother was a psychiatric social worker. His parents instilled in him a keen political and social awareness, particularly for second-wave feminism and the notion that good-works were part of the social contract.

Emerson played a key role in Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 run, serving as his California campaign manager. During the administration, Emerson served officially as deputy director of intergovernmental affairs and unofficially as Clinton’s “Secretary of California.” Between Hart and Clinton, Emerson dove into local government, serving as Los Angeles’s chief deputy city attorney under City Attorney James K. Hahn. Emerson narrowly lost his own bid for office when he ran for California State Assembly in 1991. The private sector eventually called him back with an offer Emerson couldn’t refuse and he joined the global powerhouse investment firm the Capital Group (estimated $2.6 trillion in assets) in 1997 as President of Private Client Services.

Not that Emerson started shirking his civic engagements. As chairman of the Los Angeles Music Center, Emerson helped coordinate an extraordinary public-private partnership that culminated with him presiding over the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall. He has also served on the boards of a long list of civic-minded organizations, among them: YMCA of Metropolitan Los Angeles (vice chair), the Pacific Council on International Policy, the American Council on Germany (chair), the German Marshall Fund, the Ralph M. Parsons Foundation, and more.

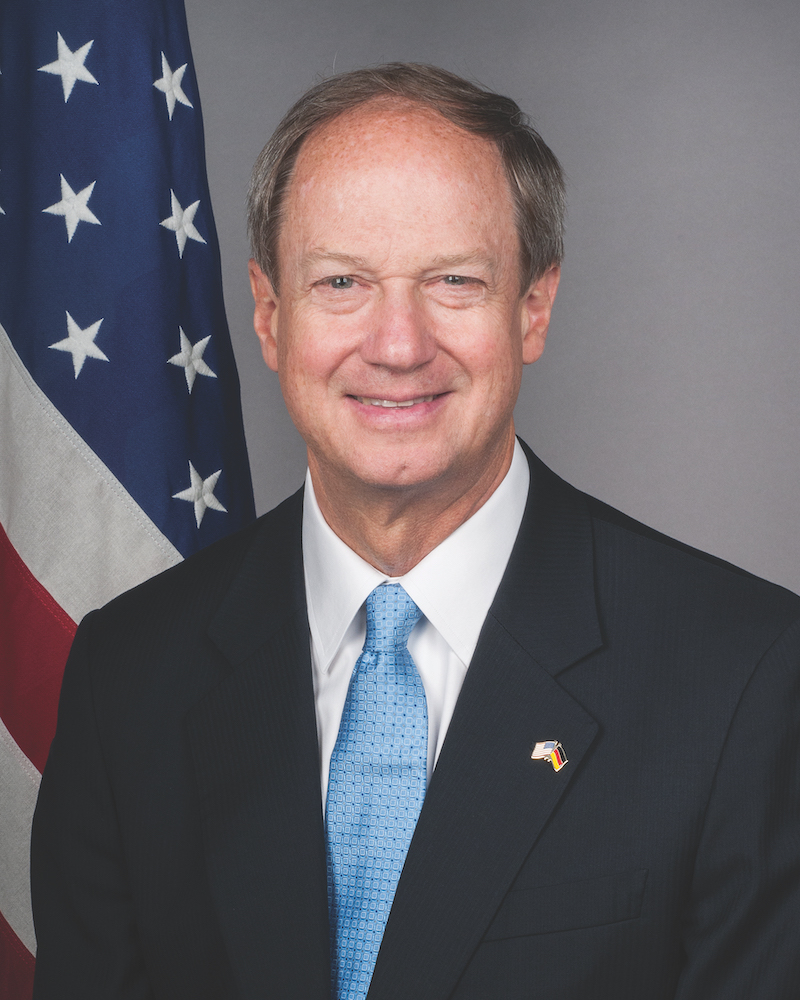

In case you’re the hard-to-impress type, I should mention that Emerson served as United States Ambassador to Germany from 2013-2017, earning the Sue M. Cobb Award for Exemplary Diplomatic Service in 2015. He was awarded the CIA Medal and the United States Navy Distinguished Public Service Award, its highest civilian honor, in 2017.

Emerson returned to Los Angeles from his diplomatic mission in 2017, rejoining the Capital Group as Vice Chairman of Capital International.

The Giving List spoke with Mr. Emerson on the eve of his pending international trip to Berlin. The following has been edited for concision and clarity.

Q: You seem to have really taken a shine to California. Did you seek out Los Angeles or were you recruited here by Manatt, Phelps, & Phillips upon graduating from law school?

A: Yes, I was recruited by the law firm, but of course, you seek out the cities that you want to look at firms in. I came to California for a couple of reasons. One, I saw it totally as the land of opportunity; I had the sense that California was a meritocracy. Nobody cared who your family was or who your connections were. It’s very plausible to come to Los Angeles and start with nothing and make something of yourself. That was appealing to me.

I remember the sense of optimism, of someone from a new generation coming on the scene with Hart that eventually manifested in Bill Clinton. How did you come to be the deputy campaign manager for Hart’s presidential run?

Yes, [Clinton] was a very natural follow up. Also young, dynamic, someone who writes books and is thoughtful about policy.

I saw that the Democratic Party was really lost in terms of its ideas, after the Reagan election in 1980. And then I saw Gary Hart as someone who was really trying to rethink everything. So, instead of fighting over how to split up the economic pie, he said let’s figure out how to make it grow. Instead of building these massive nuclear weapons – this guy’s saying this in the early 1980s – let’s build a maneuverable defense that can join in combat in multiple areas simultaneously…

He was one of the first people to really put the environment front and center. Jerry Brown was too, obviously out here in California. And I just thought, ‘Wow, this guy’s fantastic.’ Plus, he looked like a movie star. I mean, he was exciting. I thought he was our generation’s John Kennedy. And so, it turned out he was coming to town, and I very enthusiastically raised my hand and put together this [friendraising] event. And then I just told his staff people, this was back in 1982, hey, if he runs for president, I want to help. And they started calling me up to help out.

Were you always politically inclined?

That, well, it’s interesting. I know this is also about philanthropy and nonprofits and all that, but when I grew up, my dad was a minister, and my mom was a psychiatric social worker. So, certainly he was a pretty proactive minister and always very involved in the community and that kind of thing, as opposed to an evangelical preacher. I mean, he was much more a good-works type of minister and was also quite intellectual himself. His sermons were college lectures, which was great. So, I grew up in an environment where service was kind of built into the DNA, and then for whatever reason, I was just always fascinated by politics, and particularly presidential politics… I canvased for George McGovern when I was a kid. I mean, the thing to remember is political activism, when I was growing up, for many people it was a life-and-death issue because of the Vietnam War or because of abortion or more broadly, for civil rights and women’s rights.

When I came back to Los Angeles (from Washington) and joined Capital Group (CG), I was struck by the extraordinary approach towards philanthropy that CG had designed, which is very much about encouraging Capital Group associates to get involved philanthropically and then supporting them in that regard as well. That sort of opened a whole new world to me…

So, I developed a deep appreciation for the importance of not-for-profit institutions in a community – museums, music, the music centers, obviously hospitals are always incredibly important and universities and similar institutions. But to also back that up with not just board service, but to leverage financial contributions to go along with that.

Do you think that we’ve become too reliant on philanthropy to patch over what used to be public policy initiatives?

This is a topic my wife, Kimberly, has worked on a lot. You should ask her about it (see page 60). But the point is, what’s interesting to me about your question is Europeans are asking the opposite. They’re saying that we have become too dependent on solely relying on government funding and we need to expand our philanthropic outreach.

Do you think we’re at a happy equilibrium here?

I honestly think we’re at a place where we need to do a better job of letting people know the quality of what government can do so that people will be comfortable continuing to support it. We don’t have free college here, but we’re getting close with community colleges, which are just extraordinary in terms of what they can offer people in terms of education and training. But you cannot do what needs to be done without philanthropic involvement. I don’t think we’re ever going to get away from that. What I worry about is that we’ve evolved from a place where institutions in the for-profit world – think mainly large businesses, corporations, or whatever – felt a part of their corporate responsibility was to help build the communities around them, and now those institutions are getting bifurcated, or they’ve gone away, or they’ve broken down or broken up. And what’s replaced them are less institutions in the philanthropic world and more individuals… Now, it’s not necessarily about whether this community needs a hospitalor this community needs an art museum that can reach out into the community, or we need charter schools or other brick-and-mortar projects. It is what the individuals who now hold sway are interested in. Now some, like Eli and Edye Broad, were very much community builders (Walt Disney Concert Hall, The Broad, LACMA, MOCA), but that is increasingly rare.

Is there some way that philanthropy and nonprofits can help us navigate through this tenuous period that we’re in?

I think first of all, by giving voice to some of these issues. By stepping up and actually doing something about real-world problems that exist and helping people. I’m on the board of the Ralph M. Parsons Foundation, and Parsons prides itself on focusing completely on our Southern California region, but they also pride themselves on being a convener of other nonprofits. And so, for instance, Parsons will say, find a problem and decide to make a contribution to it and then bring others together and say, “Hey, this is a hole that exists in this area of social service,” or whatever. And an example of that was during COVID, Parsons ended up helping to raise, I believe, around $40 million to help keep small arts institutions in the Los Angeles metropolitan area afloat during that period.

So, I think the major philanthropies can play a crucial role because – whether it’s education or healthcare or foster children or medical care to people in underprivileged communities – they can see a problem that isn’t being addressed, or bring attention and guidance to a small organization that is addressing a specific gap in the social safety net.

I’ve long felt that, in terms of accepting the burdens and privileges of the 21st century, Los Angeles was at the forefront of our country. I’m not so sure anymore, mostly because of the cost of living here. Are you still bullish on Los Angeles?

Oh yeah. I’m definitely still bullish on Los Angeles. I think there are a number of things we’ve got to deal with here. The homelessness situation is one and the cost of housing is another. But Los Angeles is an extraordinarily diverse city in a very positive way.

I mean, what’s interesting is the places where people are most afraid of immigration are the places where they haven’t had it. Places where they have lots of immigrants are living perfectly fine with it. There are a lot of fun facts about the number of Fortune 500 companies that were founded by immigrants and the number that are run by immigrants today, or at least maybe next-generation immigrants. Cities with large immigrant populations are doing well. So, I’m definitely bullish on the diversity of Los Angeles.

I’m a little concerned about the housing price situation, and I think we’ve got to do a better job of density and mass transit and all that. I think that would improve the life of the city. But we’ve been making a lot of those investments, which will be positive. And there are a lot of good people here who care.

When I was on the Capital Group Philanthropic Committee, now they call it Capital Cares, and then being on the Parsons board, you see so many groups and organizations and nonprofits coming in and talking about what they do, and they all have boards and they’re all different people on those boards and they have staff and they’re all different people. And it’s really pretty remarkable how many people there are out here who really care and are working hard to try to make a difference and impact people’s lives in a positive way.

And that makes me feel bullish on Los Angeles.