Harnessing Philanthropy to Help People Grow Older With Dignity

“Did you know,” Rabbi Laura Geller asks, “that on average, 10,000 people turn 65 every day in the United States?”

As one of the fastest-growing demographics in the country, people 65 and older will outnumber those under 18 for the first time in history by 2035.

As one of the first female rabbis ordained in the United States in 1976, Rabbi Geller tackled gender inequality in the synagogues. Now, at 73, and with no signs of slowing down, Rabbi Geller is taking on another systemic foe: ageism.

Even though many people are aging and living longer, older people remain, for the most part, invisible to the rest of society, says Rabbi Geller. Or worse, the butt of jokes.

Geller is trying to change minds and systems to view older age not as an age group that is passing off the scene, but as a new and engaging chapter of life.

For the first time, five generations are alive today: The Silent Generation, Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z. To Geller, this is an opportunity to break the silos separating demographics and move toward a more age-inclusive culture.

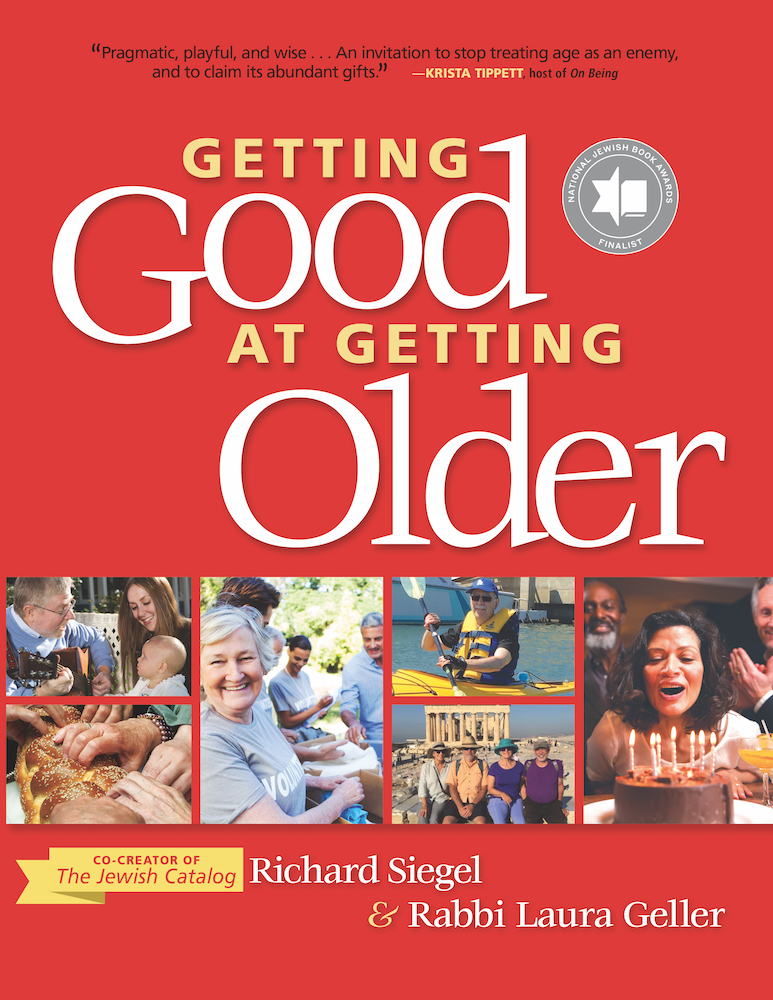

The Giving List spoke with Rabbi Geller, the author of Getting Good at Getting Older and who was twice named one of Newsweek’s 50 Most Influential Rabbis in America, on the importance of aging gracefully, with dignity and autonomy.

Q: How did you become interested in helping people grow older with dignity and autonomy?

A: I was the senior rabbi of Temple Emanuel of Beverly Hills. Back then, I noticed that a lot of older congregants were leaving the congregation. To learn more, we launched a listening campaign in 2014 and spoke to about 250 of our members between the ages of 55 and 80. I discovered that the stage of life between midlife and frail old age – often thought of as retirement years – is kind of an invisible stage. So, we asked the members questions like: Do you consider this a new stage of your life? How do you feel about it? What keeps you up at night? What gets you up in the morning?

What did you learn from those questions?

People spoke about things that they had never spoken about before. They spoke about their fears of getting older and concerns about the people they love. They shared their hopefulness about what this stage would be like. People now had the time in their lives to ponder questions about meaning and purpose.

How interesting. People live so much longer today.What are some concerns people have as they age?

Now, you can live more than 30 years between the time you retire and the time you reach frail old age. That’s long enough to experience a whole new life. A lot of people at this age have fears of becoming isolated and experiencing loneliness. They worry about becoming invisible to society and have expressed concerns such as “I was the senior rabbi of a major congregation, and now nobody knows who I am,” or “I was the dean of a law school and now nobody returns my calls.”

A lot of people think about their purpose and wonder what they will do during this stage of their life. People need a reason to get up in the morning. Some find it in giving back to their community, others in lifelong learning, still others through recreation, reconnecting with a hobby, or following up on a bucket list. Many people ask the question: With whom do I want to grow old? What the majority of these congregants, like most other active adults around the country, wanted was to age in place. They wanted to stay in the home that they loved. But in order for that to happen, we had to make some changes to the Jewish community.

How was the synagogue able to help people age in place?

We started a virtual village. It is based on the village movement (https://www.vtvnetwork.org), where a group of older people who live near each other intentionally create a virtual village, where neighbors help each other out with household tasks, rides to appointments, and a robust array of social opportunities that take place in each other’s homes, and in the community where they live – enjoying movies, theaters, museums, and lifelong learning together. When people are part of these types of villages, research has shown that their quality of life goes up, the rate of hospital recidivism goes down, and there are all sorts of other positive outcomes. In fact, a village is a response to the epidemic of isolation and loneliness that the Surgeon General recently described as a major public health crisis.

A good synagogue should be a village. So, we applied for a grant. With another congregation in Los Angeles, we created the first synagogue village in the country, called ChaiVillage LA (https://chaivillagela.org).

The village is open to anyone in the congregation, but primarily people 55 and older. You opt into it, as opposed to opting out of it. What we discovered was that people who had been leaving the synagogue chose to stay, and other people who were not members of the temple chose to join the synagogue in order for them to be part of the village. This is now our seventh year. We have 250 members who live in their own homes and pay a small amount of money to be members of the village.

Can you explain the difference between your village and a retirement community?

A village is not a retirement community. You stay in your own home. I can stay in my own home until I can’t take out my trash or change my smoke alarm battery – unless I have a neighbor who can help me. I want to stay in my home for as long as I can. I, like so many others, want to live in an age-diverse community. I want to have younger friends. Often a retirement community doesn’t offer that. Another difference is that so many people of this cohort want to serve, not be served. They want to help each other and don’t want to be treated like they are patients. I am not dependent or independent. I am interdependent, sometimes needing help and sometimes giving help. I want to give. I want to have agency. Some members of ChaiVillageLA are experts in constitutional law, others are experts in flower arranging – they want to share their knowledge and skills with others. They want to teach each other, learn together, and have fun together. They are building a community of active adults, who have talents and wisdom and are working together to find meaning and purpose, and to thrive for the next 30 years or longer.

As people live longer, this stage of life is a new opportunity for a whole new chapter of life. What are people calling this stage?

Exactly. This is a chance to reimagine this stage of life as one of opportunity, as opposed to one of decline. But unfortunately, there isn’t an agreed-upon name for the stage. Often, it is called the retirement years, but that only works if you actually worked. And not everybody did. Other names include the Encore generation, the Third Chapter, Renewment, and Perennials. The good news is that there is a whole new universe of people interested in this aging path of life. The New York Times published an important piece recently in its Sunday Edition called, “Can America Age Gracefully?” This is not a chronological age but a new stage. And it is not just about people who are in this stage of life now. We are actually creating a new map of life. Someday, people who are millennials now will be in this new stage; they are watching us to see how we do it. A lot of people are starting to really think about what this new stage of life can be like. Because society is at a time in history where older folks are the fastest-growing population, and so many people are living longer.

How can philanthropy play a role in helping people age gracefully?

Philanthropy needs to pay attention to the active aging population. This cohort has been essentially invisible until recently. Major foundations now look at diversity, inclusion, and equity. They should also be looking at age. I recommend philanthropists view funding opportunities through a co-generational lens. In other words, when considering issues to address, think of ways funding can be inclusive of all age groups. I would like to see opportunities for generations to be mixing more. Research indicates that younger people want contact with older adults beyond their families, and older adults want to be connected with those younger than they are.

Some of the challenges include that it is difficult to meet people of different ages because the U.S. is now the most age-segregated country in the world. Synagogues, churches, and other religious institutions are one of the last multi-generational species in our country. Another challenge is that older adults often think of themselves as holders of wisdom that they want to pass on to the next generation. But instead of thinking “from generation to generation,” we should be thinking of “generations working together.” The world is too complicated for one generation to try to repair it alone; we need to work together to face the enormous problems of social justice and climate change now. Another challenge is that many older adults are great at giving advice but not great at listening.

What are some examples of breaking down the silos of generations?

One is in the workforce: There is an increasing body of evidence that mixed-age teams in the workplace are more productive than teams of workers of the same age. Another is the move of some universities to pay attention to lifelong learning, creating opportunities for older adults to become students again, along with 18- to 21-year-olds. Another relates to housing. There are some exciting innovations around home-sharing and multigenerational housing. For instance, there’s an app for older people to find short- or long-term housing with younger adults. I share my house with students studying to be rabbis. And we both benefit. It’s just incredibly wonderful for me to be engaged in the world of younger people – and it’s good for them too, both financially and socially. We can learn from each other and become friends with each other’s friends. Instead of a small, overpriced apartment, they have a whole house that becomes theirs as well as mine.