Wilma Melville: Dogged Determination

Wilma Melville is the most inspirational person I’ve ever met. She has done more during her retirement than most people have done during their entire careers. I recently had the pleasure of visiting her at the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation Training Center in Santa Paula, California, and then again in the hangar where she lives with her airplane. “Spark plug” is an overused term I have never used before. She is a spark plug. She is Annie Oakley. She is Amelia Earhart. Above all, Wilma Melville is an exhauster of my internal thesaurus of superlatives.

One of the things I find so inspirational about Melville is she has achieved so much without having any particular advantages. She was a public school gym teacher from a working-class neighborhood in Newark. If there’s one advantage Melville thinks she had, it was her grandmother Pauline who mentored her and cared for her during the summers of World War II. That granny showed Melville the importance of hard work, self-reliance, and charity – attributes that would eventually blossom into the $7 million-plus annual revenue National Disaster Search Dog Foundation and training facility Melville founded more than a quarter century ago.

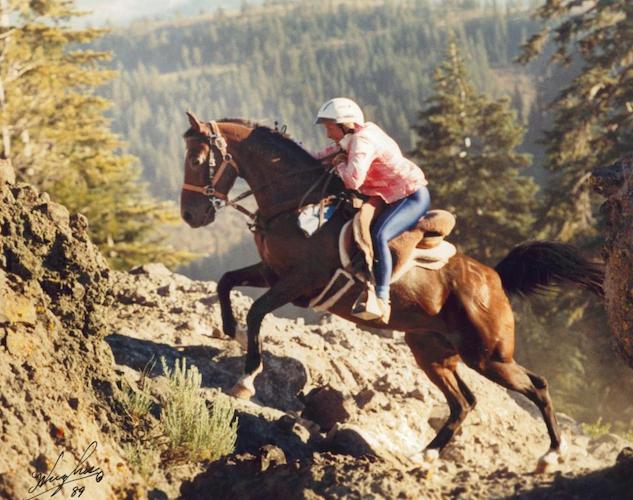

As Melville tells it, she always pushed herself and her body hard. “Lots of energy came my way from some DNA combination. Running felt so good, I wondered why so many people were walking. Right through high school, Phys Ed was my favorite class. Eventually I came to understand I had an adventurous spirit, so let’s get on with hiking, camping, and even endurance horseback riding.” Endurance rides are what brought Melville to Ojai – it was the incredible, beautiful, and plentiful network of trails. Having trained on those robust Ojai trails, Melville twice rode the Tevis Cup, a 100-mile horseback endurance ride in the Sierras of Northern California, in less than 24 hours. She has always pushed it, even now as she’s pushing 90.

This is Melville in her own words: “Living 88 years is a lengthy time with endless opportunities to learn. I’ve learned a great deal in those years. Not everything, mind you, but I’ve gone through significant changes. Some of the happenings that changed me were painful, while others took growing up and simply becoming a realist.”

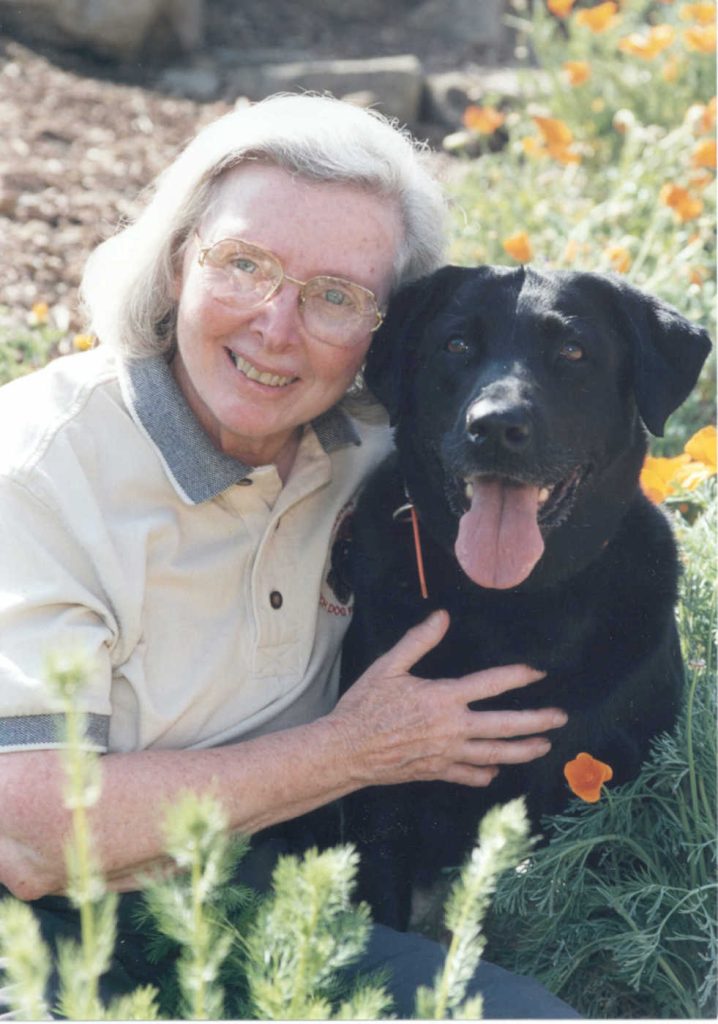

Melville’s journey to rescue dog royalty was by no means a direct path. She always loved animals even though she grew up in the city. But it wasn’t until much later when she was “retired” in Ojai and her horse got injured requiring a lengthy recovery that the always-goal-oriented Melville decided to train a dog to “do something special!” The next goal would be to attain certification as a FEMA canine disaster search team. That requires developing skills in dogs and handlers that are highly unusual – such as training dogs to climb up and down ladders, or to walk upstairs backward, or to find a missing person amid a myriad of confusing smells (including a generous drenching of jet fuel).

What especially appealed to Melville were many of the best dogs for search and rescue are those that were abandoned. “Many of these dogs would likely have been euthanized,” she says. “The Search Dog Foundation looks for dogs that are extremely driven, hyper focused, and tenacious. It’s what makes them difficult but also what makes them great. It’s just their personality. But because of that, the dogs need a lot of tasks and much personalized interaction as an outlet for all that determination and energy. Is it a surprise I get along with that type of animal? Probably not.”

Melville trained Murphy to be FEMA-certified in 24 months. Not long thereafter came the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building by domestic terrorists. Melville saw the carnage on the news and had the inkling she might “get the call.” She was right. From Palm Springs where she was vacationing, Melville was deployed for 10 days with Murphy to the federal building (what was left of it). The truck bomb destroyed that building and damaged or destroyed 424 other structures within a 16-block radius. One hundred and sixty-eight people were killed – 30 of them children in the building’s daycare facility. As Melville tells it: “I saw the best of humanity and the worst of humanity in Oklahoma. The destruction was caused by the worst of humanity, but the average Oklahoman was doing anything and everything they could to help. We – the search dogs and their handlers – were flown in on a military plane and every day our job was to go wherever the fire department and other first responders needed us. The blast had pancaked all the floors together, so as they excavated, you knew what floor you were on based on the contents of the debris. If there were adding machines, you knew you had found the accounting floor. And sadly, when we got to the toys and little juice boxes, we knew we were in the daycare.

“Every day we would go in for 12-hour search-and-rescue shifts, and every night we’d come out with our dogs, and Oklahomans would be at the gates, asking us if we had found this person or that person. I remember this one guy was there every night, patiently standing vigil, waiting to hear what happened with his wife, holding out hope. Hope can be infinitesimally small, but so long as there’s still that ember, this guy was going to be there every night. I remember one night I was coming out with Murphy and the guy stopped me, and held up a picture of his wife and said, ‘Have you found my wife yet?’ I didn’t have the heart to tell him that because of the force of the blast, we were not finding a great number of intact bodies. So I just told him we would not stop searching until every single person had been accounted for. This was true. We certainly had the tools to do that.”

Almost 30 years later, this woman who seems so tough – this modern-day Annie Oakley – quietly and undramatically weeps as she tells that story. She talks about the importance of closure, of people holding out hope. Melville continues, “When these dogs make a discovery, what it does is allow the family to close that chapter and eventually start a new one.”

From her experience in Oklahoma, Melville learned there were only approximately 15 FEMA-certified dogs in the entire United States – a completely anemic and insufficient number. So she vowed to increase that number, because the greater the number of local dogs spread out over the country, the faster they can be deployed and the greater likelihood of a “live find.” After the Murrah Building bombing, Melville created the Search Dog Foundation. The first goal was to train 168 certified canine disaster search teams – one for each person who died in Oklahoma. This was completed in February 2020 and Melville was there to witness it. Today, the number 168 is engraved on the sculpture of Melville and Murphy that stands proudly at the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation training facility in Santa Paula.

In Wilma’s Words

LF: To what do you contribute your moxie?

WM: I was an extremely shy child with many fears. I missed out on a great deal of fun, so at about the age of 12, I decided on my own that fear was misplaced energy. I had to face my fears and battle to overcome them one by one. I did just that in the way of a 12-year-old, and have honed that skill ever since. And it only took me about a century!

LF: As for your capacity to get things done?

WM: I think this is an attitude. One has to “get done what’s on one’s plate today” because tomorrow is another day. Another group of demands will be made tomorrow. If I don’t complete all my tasks today, how can I possibly handle tomorrow too? I don’t understand procrastination. Sometimes I have to think on a topic so that item does not get done today. But to push off until tomorrow what can be done today is just going to make tomorrow very difficult.

LF: Where did you get the “bug” to become a pilot?

WM: My first husband, a physician, was out shopping for a plane thinking he would take flying lessons in that plane. I immediately signed up for lessons thinking, I’ll be damned if I’m going to sit in a plane with him and not know how to fly. I had completed perhaps a dozen lessons and the guy never did buy a plane. Dilemma. Since I do not like to stop in the middle and leave a project undone, I completed the course and became a licensed pilot. Flying added a tremendous lift to my self-confidence! My thinking was, If I could fly, I could do most anything. Then came a divorce with four very young boys to raise. Yep, that was one of the tough times and difficult decisions. Fortunately that divorce was perhaps the best decision I’ve made over the years. [Three of Melville’s four sons have become pilots.]

LF: What has made you so fiercely independent?

MW: The divorce taught me that no one would ever take care of me as well as I could myself. I was enraged that I had bought into the culture of the 1950s. I was intensely angry with myself that I had even imagined that another person had to be counted on. I had worked as a teacher so that the now-divorced husband could go to medical school. He could pay enough child support so that with me teaching, the money flow was adequate. Time passed. Some lessons are more difficult than others. Eventually I met my next husband while hiking with my kids at Mount Baldy.

LF: Would you say there is value in knowing not just who you are but who you aren’t?

WM: I realize I have only normal intelligence. My education was adequate for a teacher. I recognize that I was a “late bloomer” when it came to making a change in the tiny sliver of dogdom that we call “canine disaster search.” I learned to take anger and turn it into useful energy. When a pilot in the air finds herself in a tough situation, what follows is an air traffic controller saying, “What are your intentions?” That is a sobering question. My hair stands on end. There is no one else to answer. One can delay by saying, “Standby.” But moments later, one’s intentions must be spoken. Becoming a pilot was an outstanding help in my life. I give myself credit for a vision plus the knowledge that I had to surround myself with those who knew a great deal about things of which I knew very little. To this day, I know very well the direction that the Search Dog Foundation must go. The future and the horizon are clear to me. At 88, I likely have little time remaining. What will be the best use of my time? Standby.